1) Art & Science Orchard

This mini-orchard is one of 25 planted by the Dundee Urban Orchard initiative in 2013-17. Made in collaboration with Dundee Science Centre and Dundee Contemporary Arts, its layout was inspired by the Fibonacci sequence, a numerical pattern which appears frequently in both art and nature.

Walk along Greenmarket, turn right to head past railway station, cross over Riverside Drive.

2) Discovery Point

The British National Antarctic Expedition on board RRS Discovery included important biological research by assistant surgeon, zoologist and artist, Edward Wilson and marine biologist, Thomas Vere Hodgson. The extreme conditions faced by the crew meant that the ship’s surgeon, Reginald Koettlitz, played a vital role. More info about Koettlitz, Wilson, Hodgson and the rest of the crew at the RRS Discovery website.

🧭 Head along Riverside Esplanade past V&A Dundee then cross over the road to reach the gardens.

3) Discovery Walk, Slessor Gardens

The British National Antarctic Expedition on board RRS Discovery included important biological research by assistant surgeon, zoologist and artist, Edward Wilson and marine biologist, Thomas Vere Hodgson. The extreme conditions faced by the crew meant that the ship’s surgeon, Reginald Koettlitz, played a vital role. More info about Koettlitz, Wilson, Hodgson and the rest of the crew at the RRS Discovery website.

🧭 Head along Riverside Esplanade past V&A Dundee then cross over the road to reach the gardens.

🧪 Research Today

Kevin Read’s lab in the Drug Discovery Unit (DDU), focus on understanding how the body deals with a new drug, a term we call pharmacokinetics and this relationship with what that drug does to the body, a term we call pharmacodynamics. Fundamentally, they are trying to develop a drug that, when taken by mouth, gets to where it needs to in the body at the right concentration and stays there for the right amount of time to have the desired effect and without causing any unwanted effects. Together with medicinal chemistry, they redesign and test, until they have a new drug that delivers this. In drug discovery this process is called lead optimisation and often takes several years to get to the point where we have the right overall balance of properties that warrant that new drug to go into regulatory toxicology studies and then clinical trials.

The DDU have been instrumental in successfully developing a single dose treatment for malaria and two different drugs for visceral leishmaniasis, all now in clinical trials. Learn more about what visceral leishmaniasis is and why scientists in the DDU are searching for treatments:

4) Malmaison Hotel

Near this site was Dundee’s Cholera Hospital, an isolated tenement building on the waterfront (Dock Street was the original shoreline) which the Town Council acquired in 1826. This was a time when epidemic diseases were common, and the hospital was well-used when the diarrhea causing disease cholera struck Dundee in 1832. 808 cases were reported, 505 of whom died.

Image right: The Cholera Hospital, from A C Lamb’s Dundee: Its Quaint & Historic Buildings (1895), courtesy of Tayside Medical History Museum, University of Dundee Museum Services.

Read Graham Lowe’s essay on Dundee’s Hospitals Through the Ages to learn more of Dundee’s hospital history.

🧪 Research Today

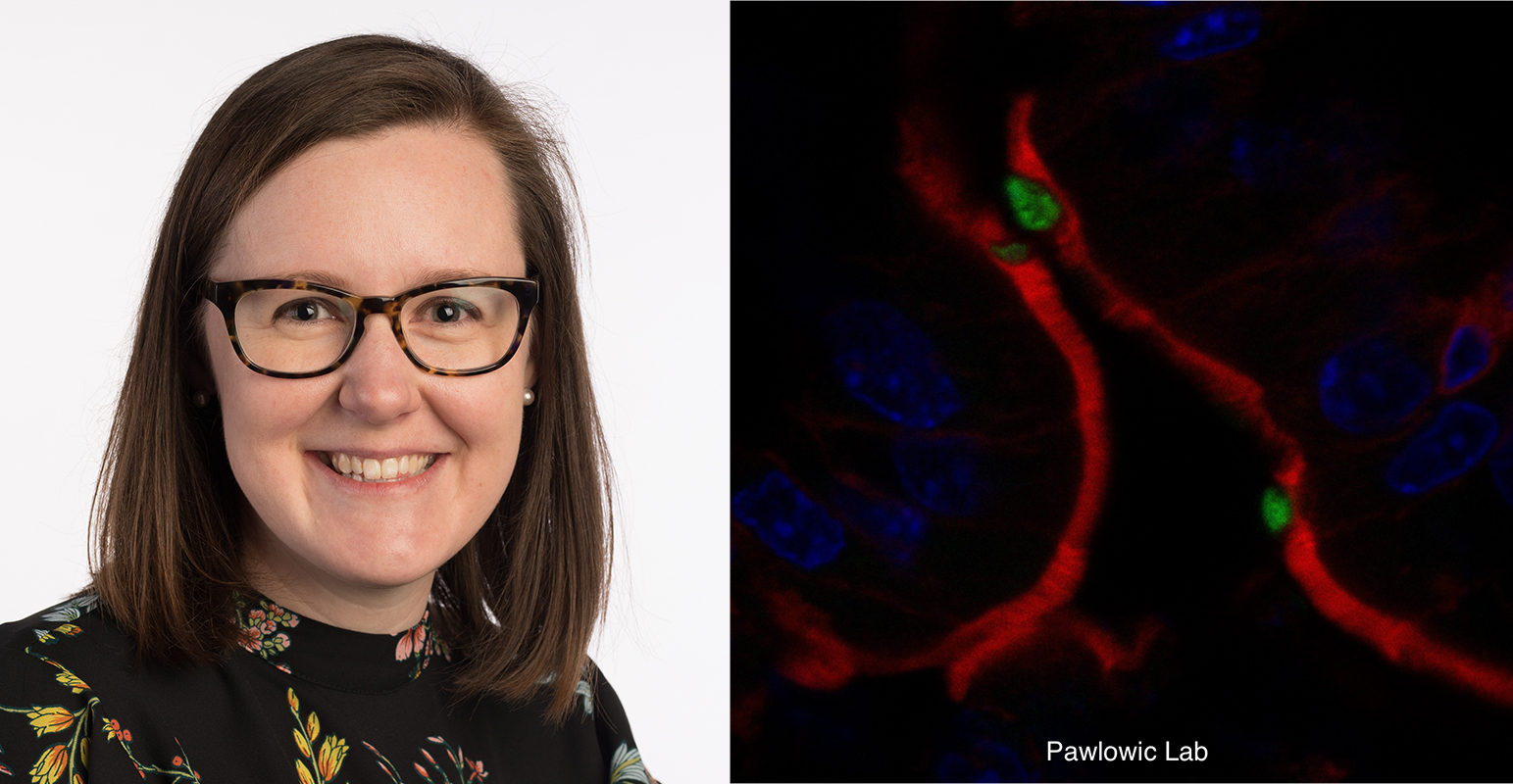

Mattie Pawlowic’s lab in the School of Life Sciences at the University of Dundee studies Cryptosporidium, a microscopic parasite that causes diarrhea in young children. Cryptosporidium is spread in dirty water and is difficult to kill- it can even survive bleach! This means that removing it from drinking water can be difficult. Usual water treatments, like chlorination don’t work. This is because Cryptosporidium is protected in a shell when it is in water. Mattie and her team are trying to understand how Cryptosporidium build this protective “egg shell”; if they can identify weak points in the shell, maybe they can improve water treatments!

5) Crichton Street

Crichton Street is named after the family of John Crichton, one of the original attending surgeons at Dundee Infirmary when it opened in 1798. He worked there for 57 years and was renowned for his skill at lithotomy to remove stones from the bladder – his mortality rate of less than 7% was remarkable in the days before effective anaesthesia and antisepsis.

Learn more about John Crichton and other 19th century surgeons.

Image: Portrait of John Crichton by John Gibson, 1841, courtesy Tayside Medical History Museum.

🧭 Head up the steps midway along Crichton Street (or for a step-free route, head to the top of Crichton St, right onto High St then right again into City Square).

6) City Square

One of the streets demolished to make way for City Square (pictured left) was St Clement’s Court, one of the homes of the Dundee Rational Institution. This was Dundee’s first major scientific body, founded in 1809. Its stated object was “the diffusion of knowledge” with scientific research and debate as its main activity – “When men pursue together the path of knowledge, the one, generally, is able to correct the lapses of the other; and they uniformly stimulate each other to more vigorous exertion.” To expand its members’ knowledge and to encourage practical experiment, the Institution boasted a “Library, Museum, and Philosophical Apparatus” Its members included many of Dundee’s most radical thinkers.

You can find out more about the Rational Institution in the Abertay Historical Society book Creatures of Fancy – Mary Shelley in Dundee.

🧭Turn right onto High Street and along to no 76.

7) Campbell’s Close, 76 High Street

Campbell’s Close was home to the Dundee Phrenological Society. Founded in 1824, it was Dundee’s first medical society, and its president was James Chalmers of postage stamp fame. The society’s collection of busts was open to members every Saturday evening. Phrenology involved studying the bumps on people’s heads to predict their personality and mental traits. Hugely popular in its day, it was largely discredited by the 1840s.

🧪 Research Today

Today, research into understanding the brain and what can go wrong takes place in Dario Alessi’s lab in the MRC Protein Phosphorylation and Ubiquitylation Unit, investigates the mechanisms that underpin Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s is a neurodegenerative disease that affects an estimated 7 million people worldwide, with the main symptoms being slowness of movement and rigidity.

These symptoms arise because of a loss of nerve cells in a part of the brain called the Substantia Nigra. One way to investigate what causes this specific loss of cells is by researching the genetic forms of the disease, where changes in a person’s DNA makes them more susceptible to the condition.

This is called familial Parkinson’s disease, which can run within families and is therefore inheritable. So far multiple genes (which are the blueprint for proteins) have been identified and linked to the disease. Matthew’s research focuses on understanding the relationship between two of these Parkinson-associated proteins, LRRK2 and VPS35. He is trying to gain a better understanding of how these proteins work, and more importantly how they become dysfunctional in Parkinson’s disease.

🧭 Turn back along High Street, head into the Overgate and turn right out the back exit. If the Overgate is closed, head up Reform Street and turn left down Bank Street.

8) William Gardiner Square

This garden area is named after botanist and poet William Gardiner, but should perhaps be named instead after his uncle Douglas Gardiner (custodian of the Rational Institution’s library and museum), who created a botanic garden near this site. Douglas and William became keen members of a new society, the Gleaners of Nature, founded in 1828 after the Rational Institution folded. William became the first person to create a systematic catalogue of local plant life (published as The Flora of Forfarshire in 1848)

In this video, museum curator Matthew Jarron discusses William Gardiner’s life and work.

🧪 Research Today

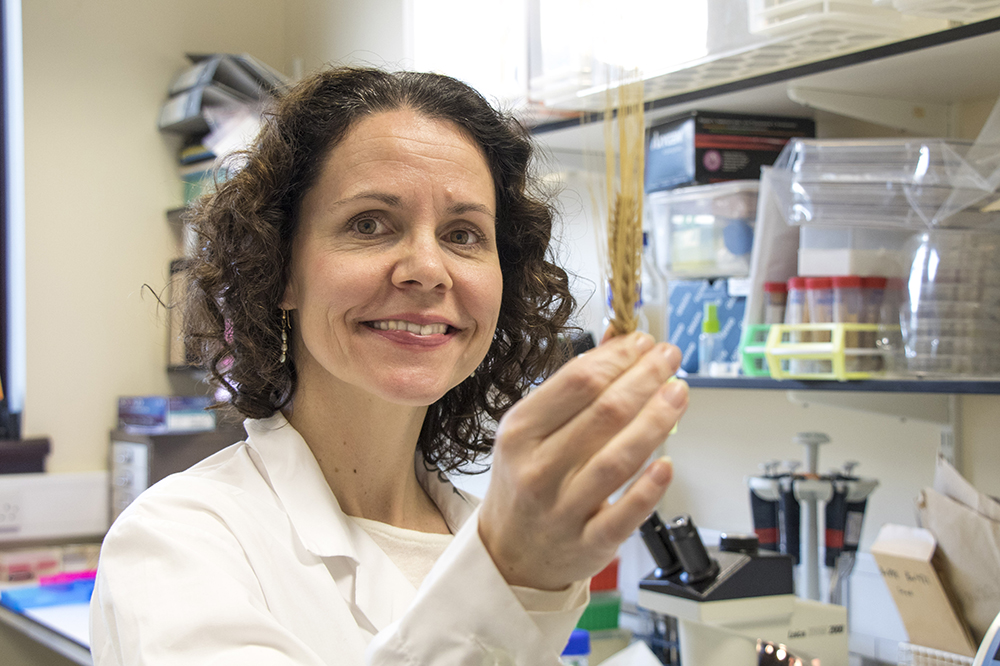

Sarah McKim (pictured right) and her lab at the University of Dundee study the growth and development of barley, Scotland’s most abundant crop. Barley has a distinctive sticky hull covering the grain, a critical feature for malting efficiency during brewing and distilling. More recent barley varieties have defective hulls which break off, a major problem for the industry. Sarah and her team are working to understand the genes and processes important for hull adherence which may reveal causes and solutions for this sticky problem.

🧭 Turn right onto Bank Street then left onto Reform Street to reach Albert Square.

9) The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery & Museum

The McManus was founded in 1867 as the Albert Institute of Literature, Science & Art. Its main hall opened just in time to host the first Dundee meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, which proved a crucial stimulus to scientific development in the town. Today, the Making of Modern Dundee gallery on the ground floor includes a display on Medicine & Biotechnology.

Image: The Albert Institute, illustration from The Angus Magazine, 1868

🧭 Turn around and head along Meadowside to the Howff.

10) The Howff

One of the many notable figures buried in the Howff is David Kinloch, a Dundee doctor who became physician to King James VI. While on royal business in Toledo he was imprisoned by the Spanish Inquisition from 1588-94. In 1596 he published the first account of obstetric practice in Scotland as a Latin poem called De Hominis Procreatione.

More on Kinloch, his obstetric practice and his tomb. Listen to Erin Farley from Dundee Libraries share the (probably fictitious!) story of how Kinloch escaped from the Spanish Inquisition.

🧭 Continue along Meadowside then turn right onto Constitution Rd to reach no 10 on left.

11) 10 Constitution Road

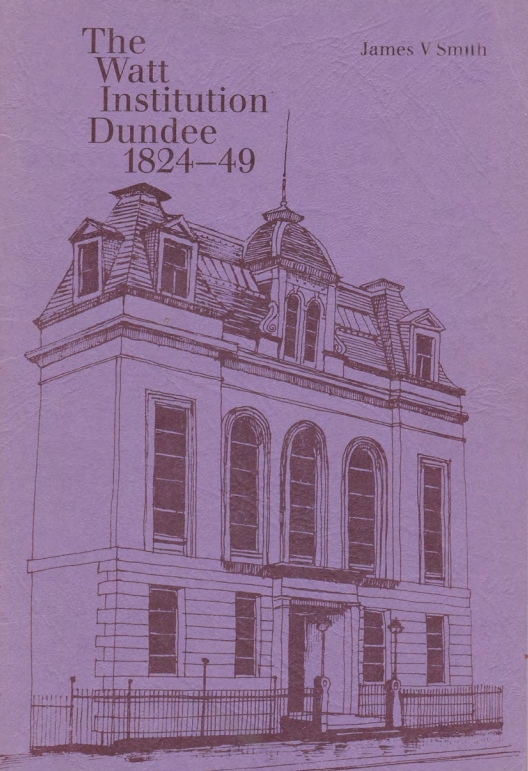

This building was originally the Watt Institution, Dundee’s first attempt at higher education. Although the building dates from 1838, the Watt Institution was originally founded in 1824, following the establishment of similar mechanics’ institutes in Edinburgh and Glasgow. It initially concentrated on teaching maths, chemistry and mechanics, but lack of enrolments led to it covering more popular topics such as natural history (taught by William Gardiner). It had its own museum, run by fellow naturalist William Jackson, but eventually closed in 1849.

Read the story of the Watt Institution 1824 – 49 in this Abertay Historical Society publication by James V Smith.

🧭 Continue along Meadowside then turn right onto Constitution Rd to reach no 10 on left.

12) Abertay University

Founded as Dundee Technical Institute in 1888, Abertay University has been responsible for many innovations, including Scotland’s first science-based nursing degree (started in 1975) and a pioneering Continuous Passive Motion machine for patients recovering from joint injury, designed by David Carus in 1990. Abertay also became renowned as Scotland’s leading centre for cryopreservation research, and in 2004 scientists here became the first in the world to breed a golden eagle using frozen sperm.

Learn more on all these and others firsts at Abertay here.

🧭 Go through underpass, carry on up Constitution Road then left onto Barrack Road and continue up the road until you reach Dudhope Park.

13) Dundee Royal Infirmary

Opened in 1855 (replacing an earlier Infirmary from 1798), Dundee Royal Infirmary was the city’s main hospital until the opening of Ninewells in 1974. Much ground-breaking work was done here – for example, in the 1870s Rebecca Strong transformed nursing conditions and training; in the 1920s Margaret Fairlie used radium to treat gynaecological cancer patients; and in the 1950s James F Riley revolutionised our understanding of allergies with his work on the mast cell. The hospital closed in 1998 and is now flats.

Find out more about the history of Dundee Royal Infirmary:

Learn more about Rebecca Strong and other medical pioneers in Dundee:

🧪 Research Today

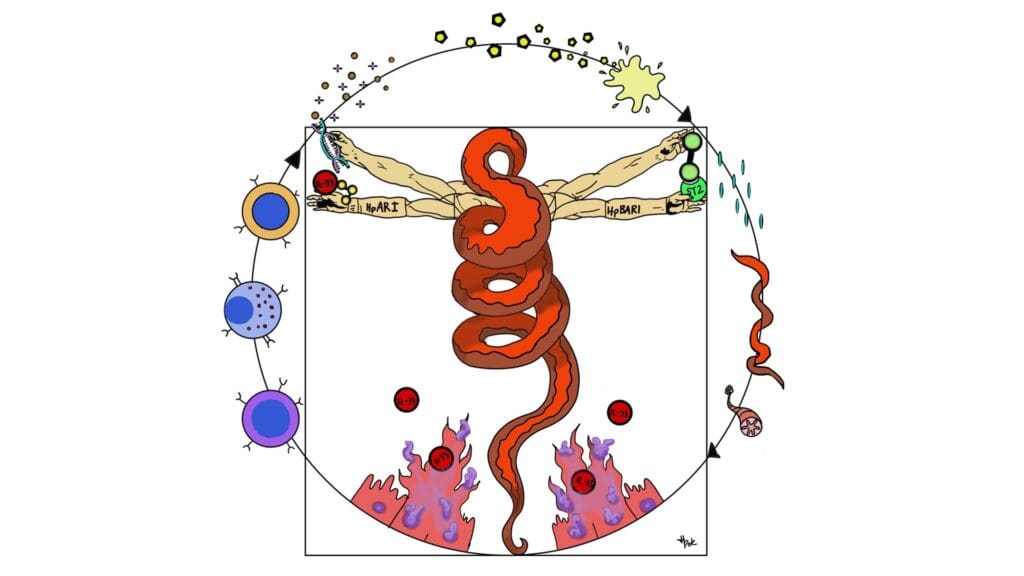

Today, Henry McSorley (pictured) and his group investigate how parasitic worms could be the key to treating diseases such as asthma. Parasitic worms are expert manipulators of the immune system. When we are infected by parasitic worms, they release various products which directly change or suppress the immune system – this allows them to survive inside us and prevents our immune system from killing them.

Although no-one really wants a gut full of worms, these infections can have a useful side-effect – people infected with worms tend not to develop asthma, and other diseases caused by a hyperactive immune response. Henry’s lab focuses on how worms achieve these effects by trying to identify the molecules that they release and using them to interfere with allergy-causing immune cells, such as mast cells. The results of such work could allow for new treatments to be developed for human diseases such as asthma.